About Virginia

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

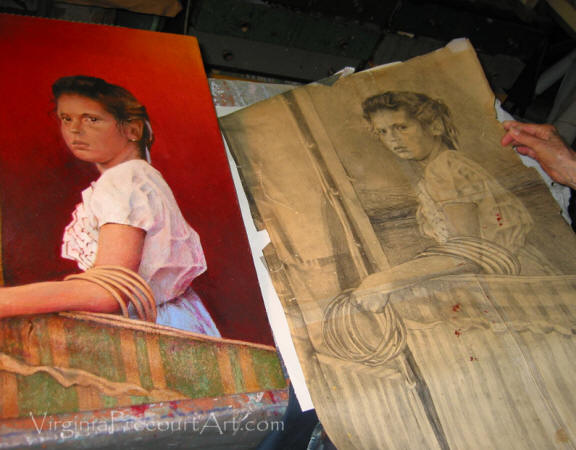

Self-portrait. Pencil on paper

“I’ve been asked so many times why in the world I went

to Afghanistan so many times,” Virginia Strom Precourt told an evening audience

at Boston’s Algonquin Club.

Her answer? “It has rocks. And I love rocks.

“Afghanistan has great, huge, beautiful rocks that are

full of minerals and has sparked civilization for hundreds of years.

“I wanted to go to Afghanistan because I work with

rocks.”

Detail: Early Risers, Rocky Brook (2004)

The country in her 2004 address largely no longer

exists. But Virginia traveled the world to find the right materials that would

advance her mission of creating work that had not just artistic integrity but

also would survive for generations.

Afghanistan had rocks that were integral to Virginia’s

work. “I grind them up and combine them with other materials to create what I

call ‘polyfrescos’,” she continued. And the stones of Afghanistan, Bhutan, Iran,

and Nepal that were integrated into her art gave her panels an extra dimension:

“Those semi-precious stones sparkled like fireflies when the light hit them.”

Indeed, the passion for just the right color in just the

right painting brought her to a small village outside Kabul: She was in search

of a special blue—"turquoise and maybe just a touch of cobalt”— that she had

seen in a book, a museum, or another piece of art. She wasn’t certain of its

source, but the vision of blue was sharp in her mind’s eye.

As she traveled toward the Khyber Pass, she recalled,

“The rocks looked like they were going to crash down on us.”

The upside: “There was a variety of colors and textures

of those rocks.

“I had hoped to find there some examples of tiles or

pottery with the kind of blue that I was looking for. And I understood it was in

this part of the country.”

Her research paid off: Though the blue mosque towers

were “exquisite,” their color was not just right. Behind an inn—a place that she

would describe as “my favorite spot in the entire world”—she found her elusive

blue.

Detail: Genesis (1967)

And, with it, a recommitment to her art: “I went there

every day all by myself. I guess the colors and the energy that seemed to be

everywhere made me feel that anything these people believed was possible.

Reality and imagination were one and the same in this land.”

So, Virginia traveled for decades—to Afghanistan,

Bhutan, Bulgaria, China, England, Egypt, France, India, Iran, Italy, Nepal,

Rumania, and Spain — often in the company of a committee of artists and scholars

from Museum of Fine Arts in Boston who shared her goal of creating art that

endures.

.jpg)

Back home in her ground-floor studio in

Dover, Massachusetts—Virginia Strom Precourt brought that special blue hue into

the sky of an Afghani street scene. In tribute, she dropped a modest

self-portrait in among the huts, the dust, and the rocks.

If the inn outside Kabul was her most preferred retreat,

her studio was a close second. Set in a corner room with expansive light from

the North and the East, it overlooked a pond that sat on the far side of a dirt

road.

.jpg)

And just as much as Virginia Strom Precourt liked rocks

of the Middle East, she enjoyed the stones, sticks, and the fiddlehead ferns

that were part of the setting just outside her windows. And, just as exotic

semi-precious gems were part of her polyfrescos, so did the natural elements of

Dover find their way into her art.

Detail: Whistlestop

The works that came out of that pondside studio traveled

as well: Virginia’s work has been featured in exhibitions at Arvest Galleries in

Boston; Boston’s Symphony Hall, the Copley Society in Boston; Vose Galleries on

Newbury Street in Boston; and the Weyerhaeuser Gallery in the Duxbury

(Massachusetts) Art Complex Museum.

When she died in 2008, Virginia Precourt’s works were

featured in museums as well private and corporate collections all over the

world. Closer to home, a massive mural is the centerpiece of a children’s museum

in Westwood, Massachusetts, the town that abuts Dover.

Neenah's Child: Maine Carnival (2003)

Virginia’s finished works, however, all begin with finely drawn sketches. Sketch after sketch of children. Sketches of birds. Of hands. Of lilies and of ponds. Of young ballerinas concentrating in their dance studies at Boston’s Cyclorama art center.

.jpg)

The drawings didn’t always have a deliberate purpose.

What she needed to bring those disparate drawings

together was light. And light—every bit as much as rocks—infused Virginia Strom

Precourt’s art. Just as polyvinyl acetates were the bonding agents that held

together her polyfrescos, so was light the element that sealed her art.

When she traveled the midcoast Maine shore or the hills

of Franklin County with her family, she would regularly command, “Stop the car!”

and insist that her friends and family “examine the light”, as her fingers

cropped a dappled roadside forest scene.

On such occasions, Virginia didn’t need a notebook or a

sketchpad. She would lock the image in her mind. And—whether it was a day, a

week, or a month later—when she returned to her studio, she gleefully would

reconstruct the moment.

And when those moments happened, she had a wall of

sketches to pick from and add substance to the light. Light is universal. Light

is permanent. Light is the soul of Virginia Strom Precourt’s artistic DNA.

The irony is that her roots track back to a part of the

country where sunlight is a precious seasonal commodity. Virginia Strom was born

in Duluth, Minnesota, in 1916 and moved to suburban Cleveland at the age of 11.

Her interest in art was nurtured at Laurel School in Shaker Heights, and

her draftsmanship was further developed when she came to Boston after graduation from

Laurel and enrolled at the Museum School in 1934.

Though Greater Boston would become her home 12 years

later, the initial fit wasn’t comfortable: Restless with the School’s

concentration of fundamentals, Virginia transferred to the Art Institute of

Chicago.

At which point,

the economy interrupted: “Two years later, I couldn’t sell a thing,"

she wrote in 2004. “My

parents declared, ‘Enough is enough’ and I had a choice: Either I come home or

try earning my own living for a change.

“I loved my

independent artist's life, but during those awful depression years I knew I

couldn't support myself painting pictures. But I could draw! I sought out

freelance commercial art assignments, mostly newspaper ads for children’s

apparel, sale items, and home furnishings. That experience taught me the

importance of disciplined productivity.

“The first of many

doors had opened to worlds of creative possibilities.”

Detail: Study for "Garden Parties" Mural #3

Another door would open when she met the man who would

be a champion of her work and her husband for the balance of their life

together. Time Inc. recruited Harry Precourt from a Cleveland advertising agency

and transferred the young family—her first son was born in 1942—to the Greater

Boston area.

According to

Who Was Who in American Art—400 Years

of Artists in America, Mrs. Precourt then pursued her passion in art and

art history at the Cleveland School of Art; the Stuart School in Boston;

Radcliffe College; and the Child Walker Art School in Florence, Italy.

Her education continued when

she joined a committee of scholars and

artists

on an MFA committee that met regularly to research the conditions that contributed

to the permanency of art.

Virginia responded to the MFA

challenge with her creation of two new mediums.

She

continued to work on the polyfrescos whose inspiration she had found in the

Middle East and Indian Subcontinent. But even as she refined the process, the

pieces were unwieldy—finished pieces often weighed more than 200 pounds—and

often took years from initial casting to finished work.

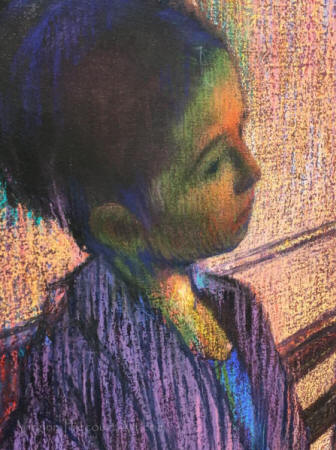

To find a new window of expression, she developed a

technique that she called “pastel-leafs” that used a gold-leaf bonding agent that

would bring permanency to pastel works that otherwise were far more delicate.

The

new technique gave new life to all those sketches and drawings

As she walked through her work space, she explained,

“Look at the beauty of that woman and that lovely color she’s wearing. And the

light around the children playing on the steps over there on the right like

children everywhere in the world.

“This young lady has the same look that interests and

fascinates me all the time,” she explains, pointing to the sketch of an Afghani

woman. “It’s universal. It’s forever.”

And from Bhutan to Boston, “I used the same pose with a

ballerina from that series of pastel-leafs.”

Virginia Strom Precourt’s own story is a tale of light shining from all corners of the world. It infuses everything she draws. And because she was a student of art as well as an artist, it will survive, even as it glows in the gallery space of WINTER LIGHT at Jan & John Maggs Antiques and Art.

—Geoffrey Precourt

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~